Pharaoh: King of Ancient Egypt at the Cleveland Museum of Art

By Christopher Alexander Gellert for love, -j.

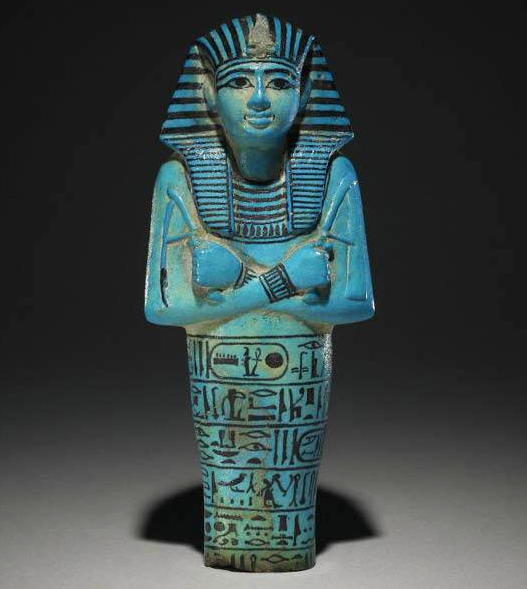

As a boy, I wandered galleries lined with elaborate

unearthed coffins -- dollhouse versions of chattel (human and material) to haul

with you to the afterlife, the rows of stiff humorless shirtless martinets mid-stride,

bedecked in serpentine headdress. I did not radiate the fascination of some of

my schoolfellows.

Picking my way through the Cleveland Museum of Art’s new

exhibition, Pharaoh: King of Ancient Egypt, I felt like one of the cats on

display: stony, indifferent, curious. Yet as I slinked through the galleries I surprised myself in wonder.

The show, organized with the British Museum and currently on

display through June 12, contains admirable works of great beauty and remarkable

craftsmanship. Seeing them through my adult eyes gave me a new understanding of my childhood

disenchantment. One cannot escape that in this exhibition every great piece of sculpture,

every fantastic monument, was built in the god-cult of a tyrant. The pharaoh's court, his pretended divinity, was the lodestone to Egyptian belief. We might remember

that Egypt’s great monuments were immense mausoleums -- the entire culture revolved

around a seemingly morbid fascination with life after death, and little concern

for this one. It’s at these kinds of thoughts that one sympathizes with

Mohammed crashing every idol in Mecca to pieces. But this impulse precludes us

from enjoyment and appreciation of works of great power – we need not embrace

them. And all of these same objections might be leveled with equal justice at

Christian art.

And yet, we cannot approach art -- even ancient art -- as

neutral apolitical relics. If art is an expression of culture, it will reflect

the political and social realities of that culture. It’s not for nothing that

the curators chose the title, Pharaoh: King of Ancient Egypt -- art in Egypt was pharaonic

Art. Each of the 10 galleries is organized around a different aspect of court

life and political theater. It reminds us that this art was used to enforce the

political order, and instill faith and obedience.

The enforcement of

eternal order has its parallel in the rigid orthodoxy of style. If so much of

Egyptian art looks the same, we shouldn’t be surprised -- the Kingdom of Heaven

is after all immutable, and if the face of the gods were to change that might

implicitly provoke questions that were better not asked. (Though, with the advent

of the Middle Kingdom the veneer had begun to crack under political

instability, and fissures are observed in the art -- by the New Kingdom you

encounter a degree of fluidity that would have been unthinkable in the old.) And

from the doggerel tone individual pieces break out and astonish, and by very

dint of their nature -- cracked, chipped and looted fragments -- they are

incapable of fulfilling their initial purpose as propaganda, disarmed in carefully

labeled glass vitrines. History has denuded them of their political import, and

frees us to enjoy them as aesthetic objects, even if the shadow of their past

hangs over them.

The massive Hathor capital that greets the visitor at the

beginning of the exhibition speaks to us in the vulnerability etched across its

face, its broken nose and bovine ears, full eyes -- its missing body, and yet

even maimed it conjures awe at the civilization that erected it.

It is a loss I do not mourn, and yet I still cherish these

shards.

Pharaoh: King of Ancient Egypt haunts

us through June 12. An accompanying photography show (through May

24th) in the contemporary galleries peeks at the leporine

reproduction of images of Ancient Egypt, its suffusion into our culture.

Photos courtesy of Christopher Alexander Gellert and the Cleveland Museum of Art.